TIME FOR HAUPT TO COME BACK | ANDRZEJ STASIUK

So what of this Haupt? This writer who is forgotten, particular, akin to no-one? What of this author of excerpts, snippets, pieces with no punch line? It’s all frayed, torn, without onset or conclusion, without distinct form. Six hundred printed pages in soft cover. Will probably fall apart from extended use. The pages will scatter. They’ll mix, shuffle as in an unpredictable game of solitaire. What is to be done with him? With this champion of the unobvious. With this slave and master of memory.

A few years ago we visited Ulashkivtsi in Podolia, where he was born over a hundred years ago. A lone ruined church stood atop the hill. He must have been baptised there. A boy came from the village, slid his hand into the gate’s crevice, moved the iron bar away and we could enter. Rubble, remains of paintings, the glare coming down from the high windows onto the debris. I took a picture. But I don’t even know if I’ve ever looked at it. It got lost in the electronic abyss. Copied, archived, among thousands of others. I will never find it. I can only remember the damp smell of old plaster and the sunshine falling from the high windows. I long for this picture but I know that I’ll probably never return there.

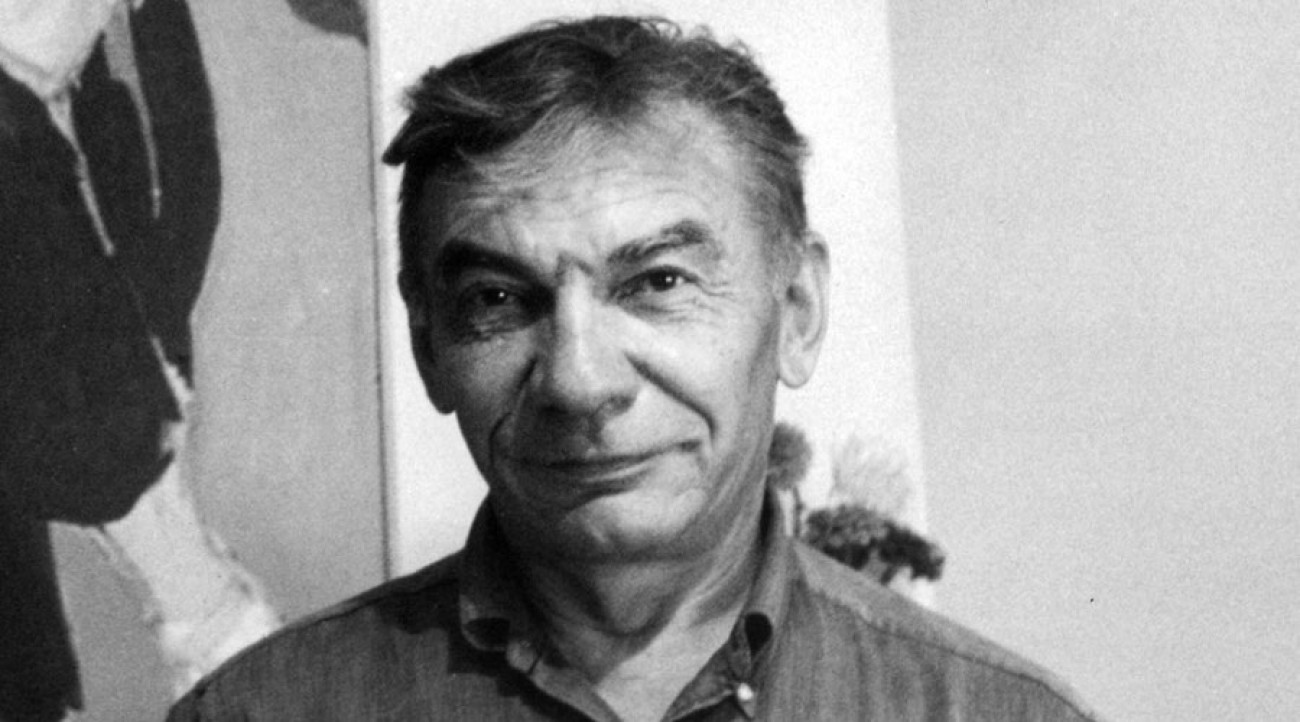

Zygmunt Haupt is a great writer. He hasn’t left any great “Work” behind. One might say he failed. Nearly forgotten, he died in exile in distant Virginia. For his first American bank loan he bought a horse and named him “Lisowczyk.” In the biographical film on the author, his friend says: “He didn’t look like a writer at all. He looked like a baker or a butcher.” He was lonely. Loneliness pervades his craft. Loneliness is his essence, the bygone – his sole topic. For these are, after all, the most important things in literature: our life, which is abandoning us.

Haupt remains unmatched. He has discovered, or perhaps invented, the language of resurrection. When he tells his seemingly static tales devoid of a distinct plot, the past is raised from the dead. We will have nothing beyond what we have experienced. Nothing else is worth the attention. The rest is window dressing, vain entertainment, and pleasing the crowd. Haupt knows this. That is why he created a language that is unsurpassed. He tells his stories in a way that makes words seem to cling to what they signify perfectly. As if memory was stronger than time, than loss, than nothingness.

You read Haupt and the lost reappears. As if one found their road to salvation. As if, for the duration of the reading, we were leaving the path that leads us inevitably to death. I do not know of anyone in Polish literature who can thus employ the Polish language to revive worlds that are seemingly gone, seemingly nonexistent. Only Bruno Schulz comes to my mind, perhaps.

Time for Haupt to come back. I believe we simply owe it to him. To condemn him to oblivion is to renounce the master of memory. Without which we are but bipedal animals that don’t even know whence they came, nor why.

ANDRZEJ STASIUK | Author, essayist, co-founder of the Czarne Publishing House, Artistic Director of the Zygmunt Haupt Festival. Writes for “Tygodnik Powszechny.” Has been living in the Lower Beskids since the late 80s. Has received numerous awards, including the Culture Foundation Prize, the Kościelski Foundation award, the Beata Pawlak Award, the Nike Literary Award, the Vilenica International Literary Prize, Gdynia Literary Award, the yearly literary award of the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage. His works have been translated to all European languages (nearly 130 translations altogether).

ANDRZEJ STASIUK | Author, essayist, co-founder of the Czarne Publishing House, Artistic Director of the Zygmunt Haupt Festival. Writes for “Tygodnik Powszechny.” Has been living in the Lower Beskids since the late 80s. Has received numerous awards, including the Culture Foundation Prize, the Kościelski Foundation award, the Beata Pawlak Award, the Nike Literary Award, the Vilenica International Literary Prize, Gdynia Literary Award, the yearly literary award of the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage. His works have been translated to all European languages (nearly 130 translations altogether).

FIND US